Bert G. J. Frederiks

The Time MachinePrototype of a Conscious Machine

3 Network instability control

Continuously changing states of neural activation in a sane and stable neural network are the result of a rather complex balance. What mechanisms could more or less guarantee, or at least attribute to this balance?

In my view my theory of consciousness is the result of some rather simple principles. But if so, then why do we need all that ‘other’ brain matter in our heads? This chapter is, among others, an exemplary answer to that.

For each known pattern a stable state of activation

How many different patterns can a neural network store? Neural networks can be built in many variations, with different properties. I already spoke about the neural network differentiating between the patterns of, for instance, apples and pears. How can these two be represented in a neural network?

The strength of the network lies in the distributed representation of the patterns which it recognizes. This is rather difficult to understand without mathematics, but I don’t think that it makes much sense for me to rewrite all the books that have been written about it. Let me try to say something about it without using mathematics.

The point is that everything in a neural network is always represented using all neurons of the network. This is in complete contrast with a computer, in which everything which is stored in memory has a specific locus or ‘address.’

To understand the principle of distributed representation, one has to realize that a neural network has a certain number of distinct, stable states of neural activation, ideally one state for every recognized pattern. In such a momentary state certain neurons are active and others are inactive. A neural network always tends to fall into such a stable state – after all, that is the definition of stable – but of course it shouldn’t keep hanging in one of them for ever.

If, with the aid of external excitation, you push the network out of a stable state, it probably enters an unstable state, which might be a state of chaotic activation, with neurons being activated and deactivated all the time, until the network as a whole falls in one of its possible, stable activation states again. Even better the network may immediately fall into a new stable state. Which stable state it falls into should be as much as possible dependent on its input – or, within limits, on its previous ‘thoughts.’

The essence of effectiveness and efficiency with regard to neural networks therefore is, what I like to call, ‘a good stable instability.’ This can be achieved in different ways.

Distributed representation in mathematical terms

I’ll give you an indication of how one can think about neural networks mathematically.

Let the activation of each neuron be a component of a vector . As such we create a multidimensional space. Vector

. As such we create a multidimensional space. Vector holds the pattern of activation of the neural network at moment

holds the pattern of activation of the neural network at moment .

.

Let us, further more, represent the sensitivity – or weight – of each inter-neural connection in a matrix . If we teach the network a certain number of patterns

. If we teach the network a certain number of patterns to

to , then

, then will generally reach such values that the network can account for all of these patterns. A linear network would achieve this at neural level by taking the inner product of

will generally reach such values that the network can account for all of these patterns. A linear network would achieve this at neural level by taking the inner product of and

and , and comparing the result

, and comparing the result  with

with again. There is no ‘central processing unit’ necessary for this process. In a non-linear network the inner product has to be replaced by some other operation, of course.

again. There is no ‘central processing unit’ necessary for this process. In a non-linear network the inner product has to be replaced by some other operation, of course.

With the result of the comparison between and

and the neural network adapts the components of

the neural network adapts the components of little by little. This adaptation takes place at neural level, not at network level.

little by little. This adaptation takes place at neural level, not at network level.

After we have taught a network the patterns to

to , we put it to the test. For this test we present a pattern

, we put it to the test. For this test we present a pattern to it, where

to it, where is an incomplete, or a distorted sample, of pattern

is an incomplete, or a distorted sample, of pattern . The network takes the inner product – or, better, some non-linear operation – of

. The network takes the inner product – or, better, some non-linear operation – of and

and . What is the result? Something which looks very much like the old

. What is the result? Something which looks very much like the old , which is known to the network. This means that the network has completed, or restored, pattern

, which is known to the network. This means that the network has completed, or restored, pattern to

to .

.

In information terminology one might say that the ‘information’ is represented in matrix . This ‘information’ is distributed all over this matrix. Therefore connectionists speak of the “distributed representation” of patterns in neural networks. You further more see, that in a neural network this information is logically not so much distributed over its neurons, but over its inter-neural, synaptic connections – that is, matrix

. This ‘information’ is distributed all over this matrix. Therefore connectionists speak of the “distributed representation” of patterns in neural networks. You further more see, that in a neural network this information is logically not so much distributed over its neurons, but over its inter-neural, synaptic connections – that is, matrix .

.

We have to distinguish between more temporary patterns and more static patterns, the temporary pattern being vector , and the more static pattern being matrix

, and the more static pattern being matrix . In other words, at a certain moment the neural network holds some temporary pattern

. In other words, at a certain moment the neural network holds some temporary pattern , while it keeps a long term memory of this in matrix

, while it keeps a long term memory of this in matrix .

.

Of course matrix is not really static. To the contrary! It is, one might say, a self-learning matrix. This matrix is a growing pattern in itself, in a sense.

is not really static. To the contrary! It is, one might say, a self-learning matrix. This matrix is a growing pattern in itself, in a sense.

As you will see, almost everything in this book is relative. Relative matters are very difficult to express, at least in western languages. Even though most people make mistakes here, I have given up trying to change our language.

The distinction between temporal and static ‘things’ will prove to be very important. Note that the title of this book is: “The Time Machine.”

Stable instability by neural exhaustion

There are a number of ways to prevent a neural network from hanging in a stable state for too long. The simplest mechanism, which works at neural level, is exhaustion. If a neuron is activated for too long, it will exhaust itself and stay deactivated for a short while after. This is a known mechanism in human neurons.

Stable instability by a deaf master of neurons

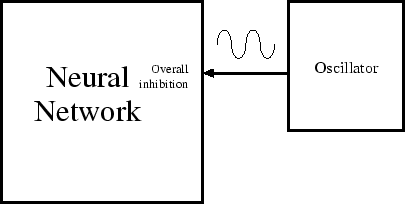

Besides master neurons there are other mechanisms to make a network more immanent. The simplest mechanism is a ‘timer.’ A timer is a master who is blind and deaf, but who tells his students to shut up nevertheless at more or less regular intervals. This has about the same effect as a master neuron, but it works less precise. In very big networks, however, this mechanism does have the advantage that it treats all neurons equal.

For a depressing timer to have any use, the network itself should, of course, always tend towards excitation. One could also fabricate it the other way round, with the network tending toward inactivation and the timer exciting it with a certain frequency. In animals, including human beings, the source of this timing function is usually attributed to the reticular system, which is a group of nuclei located in the brain stem.

This picture is much too simple however.

Stable instability by a bounding mechanism

Another possibility is a group of devices which I call ‘bounding mechanisms.’ Bounding mechanisms come in many forms. Here I’ll describe the bounding of neural activation. Further on I’ll make a device, which is capable of bounding network instability.

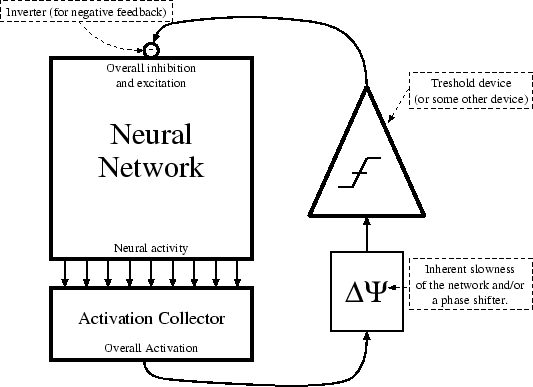

The fundamental property of the activation bounding mechanism is to bound the general activation of the neural network. In real life this is too big a task for a single neuron, but functionally it is in fact just one, very big master neuron – one might call it a ‘head-master neuron.’ Its working-out lies somewhere between that of an ordinary master neuron and a timer.

In principle a bounding mechanism could both depress, and excite a network, but in living tissue these functions are usually separated. For the moment I will not separate these functions. As such one might say that a bounding mechanism tries to keep a neural network quiet but lively.

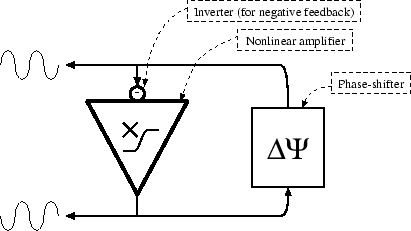

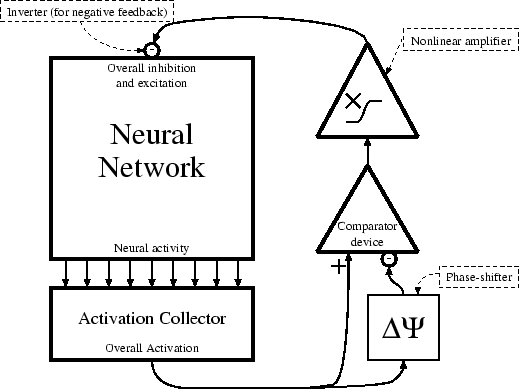

If we make the feedback non-linear enough, then, with the help of the inherent noisiness of the neural network, and the insuperable slowness of any network and any bounding mechanism, the network as a whole will tend to go into oscillation, because the inverse feedback of the bounding mechanism is always slightly out of phase with what’s happening.

An oscillator, as shown in the figure above, is no more than a phase-shifting device with an inverting, non-linear amplifier, whereby the amplifier feeds its output back into the phase-shifter. If amplification is greater than

A phase-shifter itself is just a delay-mechanism. It simply does not react very fast to its changing inputs. It must first build up a certain load within itself. This is a very simple mechanism to implement.

Stable instability by phased activation bounding

A

phased bounding mechanism feeds the inverse of the change of the overall activity of neurons back into the neural network. The net result of phased activation bounding is to keep neural activation at a certain level, whether this is high or low. This alone will rarely be beneficial.

phased bounding mechanism feeds the inverse of the change of the overall activity of neurons back into the neural network. The net result of phased activation bounding is to keep neural activation at a certain level, whether this is high or low. This alone will rarely be beneficial.

In the figure above of the phased bounding mechanism I feed the phase-shifting device not with its own inverted output, but with the activation of the neural network. This way I make the loop a little longer, so to say. If the average change in activation of the network is slow enough, input and output values of the phase-shifter will be very much alike. Therefore the comparator, which compares these two, hardly reacts and its output stays almost zero. If, on the other hand, the activation of the network changes fast, then the output of the phase-shifter won’t change as fast with it. The result is a negative or positive value at the output of the comparator. This is amplified in a non-linear way such that bigger differences in activation create even bigger signals here. The inverse of this is fed back to essentially every neuron of the network. As such the activation of all the neurons is depressed or enlarged if the change in activation of the network as a whole is either too big or too small.

One could replace the phase-shifter with all kinds of other devices. I won’t go into the details.

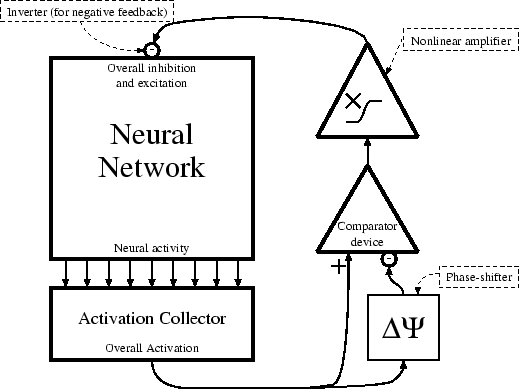

Stable instability by phased instability bounding

Externally controlled oscillation of a network can reduce the chance of the network accidentally falling into a false state of stable activation, if properly configured.

Above I had the bounding mechanism not listen to the overall stability of the network, but to the overall activation and this does not necessarily hold the right information. Remember, ‘stable’ does certainly not mean that there is no activity, nor does it in every conceivable network mean that overall activation is higher. It just means that the neurons which are active remain active, and the ones which are inactive remain inactive. As such a bounding mechanism which reacts to the activation of neurons may, in certain networks, have little value.

A network which is capable of stability will always tend to fall into the first stable state which it encounters within itself, whether this is the right one or not, for the simple reason that stable states are stable. Which of the many stable states it falls into may partly be a matter of chance. The ‘right’ state has the biggest chance, but unfortunately the others may have a chance too, and since there are many of them, we have to try to change the odds.[^]

[^]You can find more details to this argument in David E. Rumelhart, James L. McClelland, and the PDP Research Group. Parallel Distributed Processing. Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition, Volume 1: Foundations. The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1986. I shamelessly stole most of my arguments here from them.

The principle is as follows… If you start off with a high level of general neural activation, while slowly letting this activation go down, and actively preventing it from going down too fast, then there is much less chance of the network accidentally falling into the wrong stable state. For this we make the bounding mechanism such that it won’t let the network be too stable too quickly. If the network enters a stable state too fast, then it will be kicked out of it again by high neural activity summoned from above. Only the right state will be stable enough to keep hanging in. You can imagine this to yourself by picturing all the possible states of activation as a landscape with hills and valleys. The valleys are the stable states, the hills the unstable states. Only the deepest valley is, at a certain moment, the right stable state. The difference is that the neural world is not three-dimensional. It may have as many dimensions as there are neurons, in which case it would find the deepest valley anyway, but most likely not in due time.

Without something like a bounding mechanism, the network can also stabilize at a much higher level. If it would fall into a little ditch somewhere, it would stay in there because it only wants to go down. A bounding mechanism would kick the network out of this ditch again. As said above, this picture is a bit false in the sense that in a multi-hierarchical structure there will most often be at least one dimension left through which the activation can escape, but that probably won’t be the shortest route, so a phased bounding mechanism will increase the speed of a neural network, and it will do so enormously.

So, the idea is that, if a neural network ‘falls in a ditch,’ then the phased instability bounding mechanism should kick the network out of it to a limited height. This means that the network cannot get over the bigger hills anymore, but isn’t stopped by the lower ones either, both of which is what we want. This way our perception can more easily get to the essence of something.

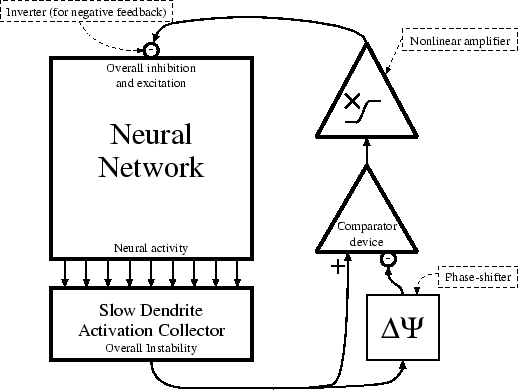

The mechanism which detects the stability of a neural network works with the aid of what I would like to call slow neurons. Slow neurons are neurons which stay excited for a longer period of time than the other neurons in the neural network. To be more precise, it isn’t that these neurons themselves are slow, but their dendrites, to which the synapses of ’pupil’ neurons connect, are. The result is that, even when neurons which are connected to a slow neuron are not activated at exactly the same time, but one after the other – as is usual in unstable states – then this slow neuron will still experience this excitement as if all of them are exciting it at ones. Therefore, the more a network is in a stable state, the less these slow neurons are being activated, and vice versa. This activity can be relayed to a bounding-like mechanism, which, in the absence of this activity of the slow neurons, that is, if a network enters a stable state, can kick the network as a whole out of this stable state again.

In the figure above we see that the output of the slow-dendrite activation collector is not the overall activity of the neural network but the overall instability.

The more instability, the more the network should be depressed. The more stability, the more the network should be excited. Therefore the inverse of the change of the overall instability is fed back into the network.

Although the slow-dendrite neurons are slow in detecting that cells around it are not active anymore, they may become activated very quickly.

Slow-dendrite feedback may work well together with a bounding mechanism which depresses or activates the network as a whole on the basis of neural activation.

Phased bounding has both advantages and disadvantages. It is likely that the amount of control must itself be controlled too. With higher frequencies – that is, shorter phases – thinking will be quicker, but also more mistakes may be made.

One must, of course, periodically allow the network to be stable and unstable. Therefore an instability control mechanism such as phased instability bounding only makes sense if it modulates itself, or if is itself modulated such that successive cycles of stability and instability are caused to occur. The idea above is that non-linear amplification plus phase-shifting is enough, but one can evidently make this as complex as one wants.

What to do with bounding mechanisms in this book

Some of the mechanisms mentioned above have the problem that they more or less assume that it takes time for a network to settle down in a certain stable state. The neurons in our brains, however, are much to slow for this. With regard to well known patterns our human neural network will immediately recognize them, or it will make only a few mistakes. The mechanisms mentioned above, would then be more useful with regard to unknown, or lesser known, or more confusing things. The essence in these cases would be that the network should find a new stable state, and learn something.

The neural machinery that I am about to make will not be able to function without bounding mechanisms. Nevertheless I do not view them as very important with regard to the themes that interests me most. Therefore I am very happy that Steven Grossberg has delved deeper into this. As you will see in the next chapter he has both constructed, and proven mathematically, that the machinery which I need for my theory works.[^]

With regard to ART neural networks Grossberg has proved mathematically that ART neural networks behave as we want in this respect, being that it immediately recognizes well known patterns but also searches for, and learns, new patterns.

[^]For an overview see Stephen Grossberg. The link between brain learning, attention, and consciousness. Consciousness and Cognition, (8):1–44, 1999. Preliminary version appears as Boston University Technical Report, CAS/CNS-TR-97-018. On the Internet you can find this work at http://www.cns.bu.edu/Profiles/Grossberg/

Further on I won’t make too many distinctions between all the different kinds of bounding. Such details are not important for the theme of this book. It is enough for me to show the possibilities.