5 Multiple and meta attention

For me most chapters in this book feel as a prelude to the next chapter. Most chapters to me also feel as a further explanation of what I had to skip in a previous chapter. This chapter is again a clear example of this. It is not the best way to write a book, sorry for that.

One might say that the previous chapter was, in retrospect, largely about Stephen Grossberg’s ART neural networks, but then explained in my words. We had a short email conversation. In his opinion “ART now has a strong explanatory and predictive record both in biology and technology, and any other model needs to beat this record, or the record of other leading models, to be viewed as significant progress.” Well, if I am going to do anything like that, then from here on it should come into existence...

The five-elements attention pattern

I will make my attention mechanism such, that it is able to attend to more than one thing at a time. If we take human vision as an example, the attention mechanism will be able to attend to five things at a time.

Five each other mutually excluding attention mechanisms can together make the neural network attend to five things at a time. Although it may – and probably does – in fact work completely different, the effect will be that it finds the five most active neurons and then excites their mirror neurons in the constructing neural network more then they might already be activated, while depressing others. As such there is a pattern of attention. This attention pattern is evidently far less complex than the sensory pattern with which it is associated.

As such, there is not only a complex, sensory pattern at the bottom of the network – plus the distributed representation following this – but also a far more simple attention pattern. These two are bound to each other, though not in as simple a way as would have been the case with singular attention.

Such an attention pattern can be remembered and retrieved consciously and almost instantly. The attention pattern can be stored and retrieved much faster, and more permanently than sensory activation patterns. After all, we do not have a truly photographic memory. This remembering makes us subjectively associating things with each other in a classical sense.

Human beings can remember the neurologically rather simple attention pattern in a matter of seconds. Whatever set of visual elements, if we can already recognize each element in it, and if the set contains less than, or equal to, five elements, then the set as a whole can be remembered almost instantly. This said we do have difficulty with more than three elements. My guess is that one or two elements are often used for the context and we ourselves. Five is the maximum, but I don’t think there is a minimum.

In non-human animals the same mechanism holds, but in them this kind of fast learning is, I think, largely dependent on stimuli like food and punishment. We, humans, can partly ‘act on’ our attention mechanism ourselves – which is both the cause and effect of our self-consciousness. Who does this ‘acting on,’ if there is no homunculus in my machine? I’ll come back to this later.

The remembering of the attention pattern is, by the way, in principle done by the network as a whole, just like with any other pattern. This said, the network at the top may have different characteristics which makes it learn faster.

The elements of the attention pattern may refer to prototypical instances of things, but they may also have their own identity, or something in between. This is like the difference in language between nouns and names.

Disregarding narrative abilities, which we have through the use of language, our instant, long term memory of concrete events must be largely the consequence of this remembering of the attention pattern – my 2021 theory has e better, more precise explanation. It is not easy to remember something which we know little about. We must first train the deconstructing and the constructing neural network, in order to be able to remember something easily, or even to perceive something consciously.

Most, if not all, people have great illusions about their capabilities with regard to their consciousness, and their remembering of things that happen around them, for the simple reason that a neural network, like our brains, is mostly complete in itself. We do not see what we do not see, and we usually do not know what we do not know, until we catch ourselves in the act, or do or say something foolish and start thinking.

Although some people think they know and can do everything, except when things are measured in a hard way, like on school, and although people may have illusions about their capabilities with regard to perception, they often come to believe the opposite with regard to things they’ve never really done, because with regard to things we do in the outside world, we are not complete in ourselves. But actually often the only reason why they cannot learn to do something is because they do not do them. I started playing the violin 2 years ago, and I must say it goes very well.

Some thought experiments

Imagine that we would have no narrative abilities. Imagine, further more, that we are in an earthly, but still completely new environment. If it is true that we remember concrete events through the remembering of attention patterns, then we would, in a situation where we do not intimately know the individual things which we see, at first associate only prototypes

[^] of these things, in stead of the individual, unique entities, and we would remember and see things as such. Is this plausible? I think it is. But these things will gain their individuality from this extraordinary situation. In the lives of most people it will be extraordinary to be in an utterly strange environment. And even if they are, one might wonder what they see and remember.

What if we are in almost the same situation each day, again without narrative abilities, how could we distinguish one day from the other? Well, do you remember instantly what you have eaten the day before yesterday? I think it is difficult without reasoning.

We do have an ongoing sense of where and when we are, and we do seem to be able to move around in an image of this.

I think that remembering what one has eaten the day before, still imagining that we do not have narrative abilities, is just a matter of association. Time can be associated with a feeling of the light of the sun, once own bodily rhythms, and other daily regularities. One’s spatial location will be fairly accurately remembered with one attention pattern per five seconds or so. Further more, here ordinary, partly transcendent, and partly immanent, long term memory comes into play too, for the simple reason that we usually are where we are for a longer period of time. A theory of how all this works will be presented in the following chapters.

It must be more difficult for children to place things in time. An important aspect of time in adults is, I think, punctuation, or what I would call the gathering of events as they happen in time. For instance, if we have had our dinner, then we usually really finish this dinner through some kind of ritual, by which it becomes an element of attention, to be associated with what we did before dinner, and what we are going to do next.

Language plays a role in this, but animals have it too, through their planning abilities.

Deconstruction, construction, sensory, and attention patterns

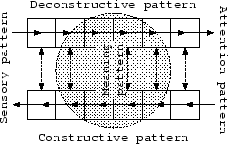

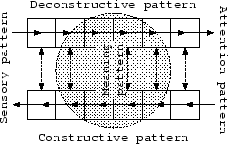

In summary I distinguish at least four types of patterns based on their locus and function in the neural network. Sensory devices provide sensory patterns. The attention mechanism provides attention patterns. From the sensory devices up to the attention mechanism there arises a deconstruction pattern. From the attention mechanism down to the sensory devices there arises a construction pattern. The deconstruction and the construction patterns tend to mirror each other, but with opposite activation flows.

The deconstruction, construction, and sensory patterns I sometimes also call images, in stead of patterns. The attention pattern is too simple to be called an image in itself, bit we may call it, simply, attention.

Reproductive versus productive patterns

Construction patterns can be more reproductive, or more productive – these terms I took form Tadeusz Kotarbiñski.

[^] In the beginning they will be more productive because of lack of knowledge. They then slowly become more reproductive. In time, when you let the network run lose for a while, the construction patterns may, through combinations and recombinations become more productive again, which we may identify with a kind of intelligence.

Construction patterns are made partly despite of, and detached from the outside world. This is especially true for a network which has a lot to learn yet. It will make ample guesses at reality. These creations will be relatively more productive and creative, than reproductive and factual. We could impossibly learn to see anything without such a bad start. The same is true for science, and so it is for the understanding and writing of this book – I will either make mistakes or bore you to death with old news.

In the same way that a construction pattern is both a reproductive and a productive pattern, so a deconstruction pattern can be more, or less the product of perception. It will at least partly be an imaginative pattern. It might even become as strong as a hallucination.

The word ‘pattern’ may be confusing sometimes. At one time it refers to a sensory pattern, a pattern which you find only at the outer borders of the lowest neural level, and at another time it refers to the pattern of activation within the network as a whole. Both are activation patterns, but I will usually only call the latter such.

Meaning patterns

The middle layers of the neural network are very powerful. They make that what we, as adults, see and do is meaningful. Not meaningful in a linguistic sense, but in a ‘sensual’ sense, in a sense that what we see is meaningful to us, in a sense that we live in a world which is not strange to us. It comes to no surprise then, that I call the patterns in the middle of the biologically fixed neural hierarchy ‘meaning-patterns.’ I know, I’ll have to spend some words to justify this.

When we imagine things, with activation starting from the attention mechanism, then it is especially in this middle area that important patterns of meaning are formed – which does, however, certainly not mean that this is what we are conscious of. What is important to me here, in this chapter, is to realize that imagination does not normally go down with equal strength all the way to the senses, neither do we experience it as such, of course. Sure, the construction neural network extends all the way down but, except when we are hallucinating, the deconstruction neural network is dominant at the sensory side. Near the attention mechanism it is the other way round; there the constructive network weighs heavier. In the middle we find our “mental testing area,” where we can judge things with our “intuition.”

As opposed to sensory and attention patterns the concept of “meaning patterns” is deliberately vague since there is not really a locus were we can find these patterns. In a sense one cannot even restrict these patterns to the neural network itself. The only thing I mean to say with the term is that in the middle of my type of neural network the concept of meaning is more important, and at the outer borders sensing and attention are more important – still disregarding narrative abilities.

Although mammals differ in their capabilities with regard to giving meaning to their environment, this is certainly not a uniquely human capability.

Reconstruction versus recognition

Our perception and memories are not exact registrations of actual happenings, like shooting a film with a camera. Either the deconstructing neural network, or the constructing neural network, or both by themselves, or both in their interaction, only learn to recognize things and regularities by encountering them rather often. How often will, because of immanency, depend on how absolutely new something is or is not. A child might need to see something strange a hundred times, while an adult needs only twelve looks at it. If you ever have needed to make a description of someone you only saw for halve a minute, even when knowing you would have to do this, then you know what I mean. Yet we do seem to recognize the person, or a look-alike, instantly, certainly if it entailed an emotionally arousing situation. How could this work?

What if there is some kind of instant memory, but not enough for reconstruction, in other words transcendent memory?

Let me first say that it is, given the current state of the abilities of neural networks, exceptional that a neural network, in this case the constructing and deconstructing network, could learn something almost instantaneously. Maybe this is, however, possible in immanized neural networks? This seems to be the case, because Grossberg has shown that for ART networks a dozen views can be enough. But then it is still strange that reconstruction of the image is not possible, so this is not the whole answer.

It might, by the way, at least partly also be that I speak here in fact of something which only occurs in high-arousal situations through a special mechanism.

Ordinary, conscious memory seems to be memory of attention. The instantaneous memory which we are conscious of, and which we remember, takes place, as it were, only at the top of the neural network. What is remembered instantaneously, is the attention pattern. One might say that what one remembers instantaneously is one’s own attention.

But the point is that this is not really remembered at the top itself, but in the network as a whole. So it is the state of the network as a whole which is remembered and retrieved, usually through some attentional association. This is just what any ordinary neural network tends to do. It cannot really do so in one step, but we do not always need that in case of recognition. For recognition we only need something distinguishing enough.

This ordinary neural remembering, within an immanized neural network, together with emotional arousal, is, I think, a sufficient explanation for the fact mentioned above, of recognizing but not remembering the looks of someone who causes an emotionally arousing situation. In part emotional arousal probably generates stronger learning, possibly at the cost of previously acquired knowledge. Secondly, the emotional arousal itself is part of the memory, and because of this, even if we have no sufficiently immanent memory, which we can analytically describe, we still have – partly transcendent – recognition, for the simple fact that we will again get emotionally aroused if we see this person.

With regard to less intense situations the same thing holds, but then we recognize something, for instance, because of vague associations which we have with regard to one thing, and not with regard to something else. Such associations will not be completely transcendent, but they are not completely immanent either.

In summary, we can remember something instantaneously because, and in so far as, the constructing neural network can construct anything new that we see out of things we already know. This requires immanence. But for recognition transcendence maybe is of equal importance.

One can only wonder how many influences slip into us through this transcendent entry. Where consciousness is lacking, manipulation lies in wait. Advertisers seem to know this.

The programming mechanism and the planning mechanism

Near the top neural level wherein the five-fold attention pattern arises, there is – I thought in 2001 – another level in which attention is (more) a singular point. If it would be just this, then we would not easily be able to know it is there. But when it contains special abilities such as some kind of feedback with temporal delay, then it will have a function.

Feedback with temporal delay at a high neural level makes it possible for a sequence of thoughts to be remembered as such.

Such a special ability could also exist on a lower neural level – it does indeed exist on a lower level too, for instance in order to see movement, and to hear changes in sounds (phonetics). The difference, with regard to the location of such special abilities in the neural hierarchy, is the direct, structuring influence that sensory information can (not) have on it. In 2001 I thought we could only find temporal mechanisms near the top and near the bottom, with the ones at the top are much more sophisticated. Now, in 2021, I think completely different about this, thanks to Don Loritz.* Temporal memory is everywhere in the neocortex.

In 2001 I thought human beings would have at least two such ‘temporalizing’ attention mechanisms near and/or above the ordinary attention mechanism; one which we share with all mammals, and which we use for planning and acting, and another which we use for language and speech. The latter mechanism, I thought in 2001, is called the “working memory” or “short term memory” in cognitive psychology. This is not correct.

In 2001 I called the working memory for language “the programmer” or the programming mechanism. I also like Lacan’s term “the Other” – with capital O – but that is so very confusing when talking about it.

[^]Subjectively this “memory,” the programmer, from moment to moment contains about seven elements, for at most 30 seconds when not repeating these elements consciously within those 30 seconds, but only one (to maybe three) of them is to the foreground from moment to moment. The prototypical example of our use of this is remembering a telephone number for at most 30 seconds – or longer if we keep repeating it within ourselves. It is very much connected to hearing and abstract abilities. I often thought of it as standing above the attention mechanism, but now, in 2021 I believe this is completely incorrect. Temporality exists in every neural column of the cortex. See my new work on this.

This programmer is not “passive.” It seemingly has some kind of “intelligence,” but this is just a special form of pattern completion with regard to temporal patterns, especially syntax. This feels like “intelligence” because the patterns are retrieved temporally too. The programmer suggests which element to put to the foreground. It does this with regard to a number of things, being the seven elements which are ‘stored’ in the programmer’s memory, the attention pattern, and with regard to other contextual factors, in other words, the state of the neural network as a whole. In the process the elements in the programmer’s memory change according to its own, syntactic rules.

Although it mainly controls itself “we” do have some half-conscious control over the use of this memory, that is the actions of the programmer.

Humans use the programming mechanism for language, but I think all mammals have something like it for planning activities, and for the recognition of the planning of others, and of other temporal happenings in the world. The mechanism is in our brains located in the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia. The basal ganglia and also the prefrontal cortex are very much involved in muscle activities of our body. The basal ganglia can produce complex, inborn ‘reflexes’ like twisting an arm or walking. It probably contains numerous neural delay pathways. In 2021 I would add that the cerebellum also plays an important role. Further more I doubt that the programming mechanism really exists as a unit; it is more something integrated in the mammal neural network.

Since the programming mechanism in humans, so I thought in 2001, is located mostly in the temporal lobe, my guess is that in humans these are separate mechanisms. We should then give them distinctive names. I would like to call the mechanism present in all mammals the planner, or planning mechanism. The language mechanism in humans I remain calling the programmer, or programming mechanism.

Although the planning mechanism must have some short term memory, just like the programming mechanism, of a view dozen seconds, my impression is that the planning mechanism does not have the ability to manipulate the elements of such a memory in the way that the programming mechanism can. Further more, the planning mechanism is much more embedded in the whole system, while the programming mechanism is really an Other.

Maybe what is special about the programmer compared to the planner is, further more, that it works more with sensory information, while the planner works more on the motor side. Or maybe the programmer really has some inborn language abilities like Noam Chomsky believes? Or maybe it is just that it is a rather separated, almost strange ‘body’ inside us, as Lacan might agree with, which makes it possible for language to have its own body, with speech arising from the interaction between this body and the rest of our body.

In humans it seems to be essential that the programming mechanism is exposed to language before the age of five or otherwise a human being will never be able to learn to speak more than two-word sentences. It seems that at least some of its content becomes more or less fixed at a certain age. But instead it may also just be that the strength of certain neural connections changes at a certain age, which makes the systems behave differently. Speech may, for instance, turn more inward at the age of five, by the programming mechanism separating itself more or less from the rest of the system, thereby allowing for people to think verbally.

Compare this to Lacan’s Other. This Other is, with the aid of our ego, and superego, a syntax-, or rule-imposing machine, enabling us to ‘serialize’ and symbolize the world.

This we have in our left hemisphere. In the right hemisphere there seems to exist a more simple, or less active version which is important with regard to music. Both mechanisms seem to be able to both detect and produce rhythm, repetition, and other regularities in time. That is temporal construction and deconstruction. No, in 2021, I see temporality as much more integrated. But humans have an urge to produce language, to imagine things, and to make music. That is our essence.

It seems to be essential that the elements contained in the programming mechanism are retrieved temporally, that is one after the other – in this the programming mechanism differs from temporal mechanisms at the sensory side of the network. The “intelligence” is in how to do this. It is in ordering its content, that is putting these elements to the foreground in a certain order. In doing so it creates certain attention patterns. For instance, as De Bono has shown, ‘dog →(pause)→ knife’ generally leads to other associations than ‘knife →(pause)→ dog.’

[^] Such attention patterns can next be taken in as a whole element again, to replace the individual elements in the working memory. This is called “chunking.”

[^] I suspect doing this efficiently and meaningfully has to be learned. The act of replacing is native to the programmer but I think parents learn their children how and when to do this. Chunking for me is just another word for punctuation and, what I call, “gathering.” I’ll come back to this in later chapters.

The programmer has important functions with regard to syntax. Intelligent, non-human animals may conceive of our speech as events of sound, and they may analyze them as such, and recognize regularities, and so on. This way they may learn to understand us a little. But for us our language is our big boss, from whom there is no escape except, maybe, into madness. For us it is something that partly, or maybe even largely, expresses us, in stead of us expressing ourselves. It both pushes and goes along with our stream of memory.

Again one can think of complex stabilization mechanisms to control this, and mental diseases in case of failures. An extreme example of language speaking (without) “us” we find in psychotic people. The opposite may be found in low intelligent, low self-control criminals; people who are to shy to open a bank-account, but who may rob a bank for millions and spend this in a few months. Our complex world must seem just as harsh to them as we view these criminals.

Possible implementation of the programming mechanism

The difficulty with regard to the programming mechanism is that it must not only remember a temporal pattern, it must also retrieve it as such. Thereby the programming mechanism must be sophisticated enough to, for instance, entail a syntax. I know too little of this to give a complete implementation, but I do have some idea’s.

My guess is that the programming mechanism consists of a special, seven-fold-but-single-spot attention mechanism, possibly connected to a more separated piece of neural network. This mechanism will hold on to seven things for 30 seconds, but from moment to moment only one of these seven may stimulate the productive halve of the neural network.

Probably this programming attention mechanism in fact consists of seven, individual, single spot attention mechanisms, with inhibiting connections in between each of them, such that each will have to attend to something else. I even think that this inhibition works such that what is attended to by each of them is as different as possible, given a certain input activation, and so on. It might be that the heart of this mechanism lies in the center of the thalamus.

A complexity with regard to the programming mechanism is that it has evolved from our hearing apparatus, and partly still has this function, next to the programming function. This hearing neural network, which is also the neural network of the programming mechanism, has a small, biologically fixed, neural hierarchy of probably three to four, or maybe seven levels. At the bottom it is connected with the ‘ordinary’ attention mechanism, with our ears, and maybe also with other, rather abstract, ‘meaning centers.’ At the top the neural network is connected to the seven-fold attention mechanism.

The programmer’s neural network is, in a sense, just part of the rest of the network, except that it is not, or not only, dominated by the ordinary attention mechanism. It may also be that the programming mechanism stands above the attention mechanism, with the hearing and programming neural network largely below the attention mechanism. This actually was my first idea. It still seems to fit most facts, if we add that it is mainly connected to the hearing part of attention – I have reasons to believe that our hearing apparatus has its own, three-fold attention mechanism. I think this will be the best solution for a neural machine, but in our brains it probably is implemented a bit quick-and-dirty.

The programmer’s attention mechanisms rely on simple recurrent delay connections of the hearing neural network. Through these our hearing apparatus can, on its own, remember things like a parrot – but it cannot on itself repeat this temporally, so maybe the parrot is a bad metaphor. The length of the sounds heard will be at least a small word-length, but it might be something like a small sentence. As such our hearing apparatus, basically contains at least a lexicon of words – that is symbols.

To create short term memory the seven attention mechanisms compete not only to make sure that each attends to something else, they should also compete in such a way that only one of them at a time can influence the rest of the brain – winner take all. This competition, however, may not hinder too much any of them in holding on to what is perceived for at least 30 seconds. A kind of self organizing mapping structure may do the trick. The competition should only influence which one will produce an image through the productive neural network. In this we might be able to find an explanation for why humans must be exposed to language before a certain age, probably the age of five, in order to be able to really learn a language. Until that age this competition might be switched off, which helps the network to get trained.

Ones one of the seven has won the competition, it puts its ‘will’ on the network, possibly through the ordinary attention mechanism, and next it will return to silence to let one of the others win, all the while more or less holding on qua attention. The others will, in the mean time, be influenced by the previous winners, and also by the rest of the network. Not necessarily so much that they change their attention, although this may lead to a very useful form of chunking. But which of the seven wins is influenced by the previous winner. With regard to all this the temporal delay connections are very helpful. Here we find the double function of hearing and programming.

It might be that what the programming mechanism does, through the above mechanism is, for instance, to repeat from moment to moment, within a fraction of a second the last words, or word-particles, which it has recognized. The idea is that it should do this more or less within the cycle of neural activation as determined by the stabilization mechanisms. As such the neural network is stimulated very rapidly by all seven, programming, attention mechanisms, but (probably) in the order in which the words were heard. This order is important for the route which the neural activation will take.

This process is a little more complex because of the chunking of words and other chunks. When I speak of a great brown animal, then in my mind this is immediately ‘chunked’ as a bear-like thing. This is something rather abstract. It is not something which I can easily express, nor is it, in this case, something which exists. This chunk will replace “great,” “brown,” and “animal.”

Thus chunking is probably largely the result of the self organization between the seven attention mechanisms of the programmer. Therefore the competition between the seven attention mechanisms should be such that the new winner somehow excludes the old ones leading to its winning. Things ‘looking like’ each other may be more or less automatically chunked through self organizing maps alone. Sometimes it seems to me that the self-organization with regard to chunking is as rude as shifting everything under well known syntactic headings of nouns, adjectives, verbs, and so on.

It is a question whether this might be sufficient to explain syntactic processes and self-consciousness. I tend to believe that the foregrounding by the programming mechanism entails a more sophisticated, temporal recurrence, but this may quite likely also stem from the planning mechanism, which we share with other mammals. If not, then syntax may have the same ground as the recognition of words. Someone with knowledge about this should be able to make this up.

Suppose you have a thought. The programming mechanism never rests, so it picks this up, mirrors it, in a more symbolic way because it is mostly connected to our hearing apparatus, and it returns an image, that is sound-images being words. It listens to this to tell itself what it has said, and corrects itself, and so on. All this leads to (inner) speech and dialogue.

The balance between our ‘ordinary’ neural network and the programming mechanism is very important. If the programming mechanism gets too strong, this may lead to psychosis by stimulating our hearing apparatus so much that we think we hear voices.

The programming mechanism is the source for dialogue; a grumbling in your head which later becomes your ‘voice.’ I think that dialogue ontogenetically comes before speech. How and why all this works so nicely as it seems to do, must have something to do with ones identification with significant others on the basis of rhythm, melody and harmony. I am told people who cannot speak have a poor short term memory, that is a largely unused programming mechanism.

The trick of all this is to reproduce, and to produce, something which was temporal as something that is temporal. Maybe the seven attention mechanisms of the programming mechanism together replace you yourself, the thing you speak about, and the person to whom you are speaking. As such they constitute your inner and outer voice toward someone.

After you have learned to speak, you won’t necessarily need your programming mechanism anymore – at least not at any moment – although in practice it is certainly still used, very handy indeed, and probably quite necessary for self-consciousness.

To tell you the truth, it would surprise me if I’m right. All this is just a guess. Now, in 2021, I think rather different about this. I do not think the planning and programming mechanisms exist as separate units. I think the temporal mechanism is and essential part of the network at a lower level. It is the product of the columnar organization of the network. But I do not intend to rewrite this book. I just comment on myself.

Meaning, metaphor, and metonyme

With regard to language one can find the process of predicating meaning upon something in a phenomenon called metaphorical predication. This phenomenon is used in speech to convey the meaning of one thing upon something else. For instance, if you say that someone is ‘as strong as a bear,’ then the strength of a bear is predicated upon that person.

In fact the use of metaphor is much more common than this. Every time that you utter a word, you both convey part of the meaning of that word upon that what you mean to say by it, and vice versa you also convey a meaning upon the word – usually acknowledging the known meaning of that word. I earlier referred to this process as structuration, a term from Anthony Giddens.

[^]In order for a metaphor to arise in the network, one needs some deliberate shifting – to use a Freudian term – of attention at the top, for example done by the programmer, without there being much change in the middle levels. As such the meaning of one thing can end up under the attention of something else. If this happens we speak of ‘a metaphor,’ or of ‘metaphoric predication,’ but the phenomenon of shifting is itself called ‘metonymy.’

One might say that metonymy is the result of pattern completion and/or chunking at the top of the neural network, while metaphor is the result of a kind of ‘forced’ pattern completion at the bottom. In both cases the force comes from the programmer.

Seemingly humans can, more or less deliberately, let the processes of instantiating and forming a new image, and taking in the result as a new, “chunked” symbol, run separately from each other, while connecting these processes again a moment later. This is the work of the programmer, and probably also of the planner. Without it, language and creativity would probably be impossible. Non-humans are, I think, not capable of this in the sense that they can do these things themselves. It can ‘happen’ to them, however, by chance or by outside stimuli.

All this may, further more, be an argument that phylogenetically the use of tools came before use of language and speech.

Lexical attention

We hear a word, for example “cow.” As such this comes to our attention. Since “cow” is – usually – associated with a cow, we will next think of a cow. Hearing a word causes us to attend to its meaning. The other way around, encountering and attending a cow, will tend to make us think of the word “cow.” With regard to metaphors I earlier spoke of newly created meanings. Here I speak of well known words and meanings.

Associating words with meanings or objects does not necessarily require a programming mechanism. We can, for instance, teach animals a direct association through techniques used by Pavlov. But an animal can hardly use this to plan and manipulate its environment or itself. Using sounds and words as tools is limited, compared to us. An animal will not build up another world than its direct environment, and feels no urge to communicate this through symbolic means with anybody.

It may seem strange that they do not even do so with single-word-like entities, for example in order to point at something – although they do so in a sense, for example when a dog barks at something it is afraid of. On the other hand, it must seem to them very obvious and pointless to point at what is evidently there. Although I often doubt on how much more animals may do with their planning mechanism, the important underlying reason, I think, is that an animal can hardly place itself in another being as it being another being, because for this it needs a programming mechanism – conform Lacan.

[^] As such mammals other than humans do not lose their childish narcissism.

The programming mechanism makes it possible for us to momentarily lose ourselves and to place us in the position of the other, with what we know of this other, and to think from that position, while a moment later ‘connecting’ to ourselves again. We do this constantly when speaking, by checking that what we are saying will reproduce the image that we want to convey in the first place. An animal can mostly only mirror its environment and objects in it, and act according to this through its instincts, but they surely also ‘mirror in the opposite direction,’ that is project their own images, including a vision on themselves, on the world and other animals, and act according to it. But all this is to be explained in a later chapter.

Bottom-bottom attention

The same way that words lead to associations, anything can lead to associations. As such anything can make us attend to itself and/or to something else. Along this simple way images in time can be formed through shifting attention from one thing to the next. Especially when this shifting is itself structured with the aid of a planning mechanism we largely have the main, non-linguistic base for temporal images, which will be one of main themes of the next chapters.